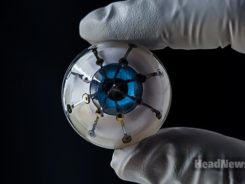

В Университете Миннесоты впервые была получена трехмерная структура, способная выявлять изменения в уровне освещенности. Структура имитирует работу сетчатки и действует вместе с имплантатом – превращает видимое изображение в электрические импульсы для клеток сетчатки, передающих сигналы об изображении в мозг.

Все это стало возможным благодаря трехмерному принтеру. В перспективе ученые хотят увеличить число световых рецепторов, чтобы повысить качество передаваемой информации. Также требуется выбрать для печати более мягкий материал, в теории пригодный для имплантации в глазницу.

На сегодняшний день ученые поняли, как печатать электронные схемы на изогнутой поверхности, что является несомненным прорывом.

Они начинали работать с полусферической основой. Используя трехмерный принтер, они покрыли его чернилами с частицами серебра. На них уже располагали фотодиоды, превращавшие свет в электричество и созданные из полупроводниковых полимерных материалов. Используя этот метод, на печать всей структуры уходит около часа.

* * *

A team of researchers at the University of Minnesota have, for the first time, fully 3D printed an array of light receptors on a hemispherical surface. This discovery marks a significant step toward creating a “bionic eye” that could someday help blind people see or sighted people see better.

The research is published today in Advanced Materials, a peer-reviewed scientific journal covering materials science. The author also holds the patent for 3D-printed semiconducting devices.

“Bionic eyes are usually thought of as science fiction, but now we are closer than ever using a multimaterial 3D printer,” said Michael McAlpine, a co-author of the study and University of Minnesota Benjamin Mayhugh Associate Professor of Mechanical Engineering.

Researchers started with a hemispherical glass dome to show how they could overcome the challenge of printing electronics on a curved surface. Using their custom-built 3D printer, they started with a base ink of silver particles. The dispensed ink stayed in place and dried uniformly instead of running down the curved surface. The researchers then used semiconducting polymer materials to print photodiodes, which convert light into electricity. The entire process takes about an hour.

McAlpine said the most surprising part of the process was the 25 percent efficiency in converting the light into electricity they achieved with the fully 3D-printed semiconductors.

“We have a long way to go to routinely print active electronics reliably, but our 3D-printed semiconductors are now starting to show that they could potentially rival the efficiency of semiconducting devices fabricated in microfabrication facilities,” McAlpine said. “Plus, we can easily print a semiconducting device on a curved surface, and they can’t.”

McAlpine and his team are known for integrating 3D printing, electronics, and biology on a single platform. They received international attention a few years ago for printing a “bionic ear.” Since then, they have 3D printed life-like artificial organs for surgical practice, electronic fabric that could serve as “bionic skin,” electronics directly on a moving hand, and cells and scaffolds that could help people living with spinal cord injuries regain some function.

McAlpine’s drive to create a bionic eye is a little more personal.

“My mother is blind in one eye, and whenever I talk about my work, she says, ‘When are you going to print me a bionic eye?’” McAlpine said.

McAlpine says the next steps are to create a prototype with more light receptors that are even more efficient. They’d also like to find a way to print on a soft hemispherical material that can be implanted into a real eye.

McAlpine’s research team includes University of Minnesota mechanical engineering graduate student Ruitao Su, postdoctoral researchers Sung Hyun Park, Shuang-Zhuang Guo, Kaiyan Qiu, Daeha Joung, Fanben Meng, and undergraduate student Jaewoo Jeong.

The research was funded by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering of the National Institutes of Health (Award No. 1DP2EB020537), The Boeing Company, and the Minnesota Discovery, Research, and InnoVation Economy (MnDRIVE) Initiative through the State of Minnesota.